Come on, admit it, British bread is much better than this Italian stuf…

On a recent trip to the UK, i finally found something that i mis; it’s a nice fresh soft load of Mother’s Pride from the local supermarket.

Processed food, probably filled with all kinds of weird modified, life-threatening chemicals, but doesn’t it taste good? It makes perfect toast, lightly grilled with butter or, better still, a real treat with the centre pulled out and rolled into a ball in the palmo f your hands and then eaten in one mouthful. Delicious. It i salso a really good way of clearing your hands. Admittley, your local branch of Sainsbury’s or Waitrose is more likely to be offering French baguette or Italian ciabatta but at least you can still buy unhealthy bread in Britain if you go to the right places. You can even geti t in restaurants. Well, i say reastaurants but you know what i mean, those places where you can get a real English breakfast anytime of day.

Actually, Eglish breakfast is another thing i miss, but i’ll tray and stay focussed on the bread. On my recent trip, i was reminded that Englsh breakfast even comes served with a dollop of brown sauce, unless you are really quick and stop them, but who is that together at 8 am after the insanely early Pisa_Liverpool Ryanair flight? But then who said there is no remaining traditional colour in the UK? An equivalent activity in one of the villeges of the Garfagnana Valley would have us all trekking up there in search of some local caracter and maybe a glass of grappa as we head for the door. But try buying a grappa anywhere else in the world but Italy and you will run into problems there must be a reason for that? Sorry, i am getting diverted again.

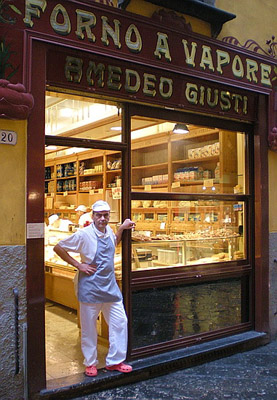

Sure, you can get approximations of soft bread in Italy. Conad makes one which isn’t bad when it is fresh. Giusti’s, the excellent bread shop in Lucca, however, singularly, fails to come up to the mark in the field of unhealty processed bread, in spite of being an otherwise impressive operation.

Just off Piazza San Michele, i have never seen such a popular shop. It can be quicker getting served in the bank than buying your daily bread from them. They have an unusual queuing method where everyone who arrives after you seems to get served first.

But i suppose it at least helps you learn to mix it with the locals; either that or starve. They also have unusual names for the bread, boy Scouts? Militari? What is that all about? Give me a couple of baps every time.

But their bread is admittedly excellent; crusty, fresh, tasty, it even has salt in it. And Giusti’s flour is a prime ingredient, brought in fresh from the wheat fields of the Padana river basin, or somewhere, and lovingly prepared by committed professionals. Just think of a Mulino Bianco advert to get the full effect of the image i am trying to create here. You know the thing, crusty bread with rich green olive oil dripping down your chin as you take a bite, sorrounded by laughing children and old folk gathered around the farmhouse table.

So what is my problem? Why the login for the processed aquidgy stuff which is about as good for you as a dose of Swine Flu?

I’m not saying that Mother’s Pride is a real alternative to fresh Lucchese bread. Even if it does fit in the toaster it still doesn’t absorb the olive oil. I’ve tried; it still doesn’t absorb the olive oil. I’ve tried; it all just drips off leaving the bread completely unmarked.

So iìm not really sure where the login for nasty processed British bread comes from and what it says about my mental health. But it is there so i guess it is just something i need to deal with and try to accept what is probably obvious to all for you: That you cannot really compare production line bread with something produced by an artisan. It is like comparing a Ford Focus with a Ferrari.

But then again, which one would you choose if you actually needed to drive somewhere?

(Mauro Vincent)

Antico Forno Amedeo Giusti:

Via S.Lucia 18/20 – 55100 Lucca

Tel: 0583 496285

e-mail: fornoavapore-giusti@luccavirtuale.it