You’d think they were giving them away to witness the annual stampede to specialty restaurants and gourmet shops up and down the Italian peninsula where customers become positively unruly elbowing each other out of the way to get served first.

On the contrary, the divinely pungent white truffles of Piedmont and Tuscany are practically worth their weight in gold. In season, fresh, first quality truffles will easily fetch 3,000 to 4,000 euros a kilo, and it takes just one taste of a risotto or omelet dressed with shavings of white truffle to acquire a lifelong unbating passion for this shy tuber.

Truffle worship is not a new phenomenon – the ancients considered these delectable comestibles to be the “undisputed king of the table” and, better still, a potent aphrodisiac. In their writings, such luminaries as Pliny the Elder, Pythagoras, Epicurus, Plutarch and Nero waxed ecstatic over them.

Alexandre Dumas once declared that if a truffle could speak it would say, “ Eat me and adore God.”

No wonder there has been chronic skullduggery and backroom brawls among truffle hunters over the centuries.

Though recently formed professional associations have established standards, required hunter sto be licensed and keep a tight control over prices in order to eliminate disputes and other unpleasantries, each year the newspeapers carry shocking stories of hunting dogs being poisoned or other crimes of violence or intimidation in truffle country.

For all the hoopla surrounding them, truffles are a most unassuming plant. Potato – like in shape, they are a subterranean fungus which grows on the roots of poplar, linden, oak and hazelnut trees. They can bea s small as a walnut or as large as a grapefruit.

There are said to bea s many as seventy varieties throughout Europe, from Portugal to the Czech Republic, and they can even be found in North Africa and Sardinia. Entrepreneurs have long attempted to develop techniques for commercial cultivation, such as inoculatine soil with fungus spores, but the secrets of the symiotic relationship between the tuber and its host tree and the surrounding conditions continue to elude them and they have met with only limited success.

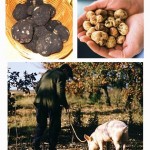

As it has been throughout history, durino the months of November through January when truffles reach their peak aroma and maturità, it still remains for the truffle hunter and his four – legged companion to forage in the wild, through forest, over hill and dale, in search of the elusive truffle. Traditionally, especially in France, it was the farmer’s pig on a leash who hunted the truffles, with the farmer in hot pursuit. When the pig started rooting in the soil to get at the subterranean treasure, the farmer would drag the pig away bifore it had time to consume the precious tuber and then he would finish the digging.

Nowadays, for the most part, the pigs have been replaced by well-trained trufflehunting dogs who are happy with only a dog biscuit as a reward. Of all the truffle varieties, the two most prized are the black Tuber Melanosporum pound primarily in France and the white Tuber Magnatum found i the Piedmont and Tuscan regione of Italy.

Surprisingly, the two are vastly different in every aspect, not just color. The black truffle, whose outer skin sometimes has a honeycomb-like texture, has a mild but distinct aroma and nutty flavor. It is almost always marinated or cooked and then added to patés, terrines or the classic Périgourdine sauce.

White truffles, on the other hand, have a smooth outer skin and an intoxicatingly strong, distinct, some would say, primal aroma. I’ve been told it is againts the law to carry them on public transportation in Italy. White truffles should never be cooked. They are shaved raw over cooked risotto, pasta, omelets, cheese fonde, Florentine steaks, cannellini beans and other vegetables.

Gourmet alimentari and butcher shops in Lucca, and hill towns such as Volterra and San Miniato al Tedesco ( which are the prime Tuscan areas for truffle hunting) offer for sale wonderful truffled pecorino cheese, fresh truffled pork sausage, fresh ravioli pasta filled with ricotta cheese and truffles butter. ( From personal experience, I do not recommend prepackaged jars of truffled butter or truffled olive oil. )

Many of restaurants in and around Volterra and san Miniato al Tedesco offer unforgettable truffle meals.

When purchasing fresh white truffles, be sure to choose ones that are firm to the touch with a distinct aroma. Spongy truffles, be sure to choose ones that are firm to the touch with a distinct aroma. Spongy truffles, like spongy potatoes, are too old. Fresh truffles are cleaned by brushing them lightly with a soft brush or soft cloth.

They should not be washed unless coated with dirt. Fresh truffles have a short shelf life – they should be washed unless coated with dirt. Fresh truffles have a short shelf life – they should be consumed within a week of purchase. If not eaten immediately, wrap the truffle in kitchen toweling, seal in a glass jar and place in the vegetable crisper of the refrigerator. White truffles are sliced paper thin with a handheld tool known as a tagliatartufi , usually available at truffle fairs, gourmet shops or kitchen specialty storse.

Buon Appetito!